Coral continued to openly ship Russian oil sourced by Rosneft. In October 2020, it transported a massive 100,000 metric ton shipment from Taman, a port on the Black Sea, according to internal documents. Then in 2021, it was reported that Coral would take over the shipping of Rosneft’s diesel and liquefied natural gas to Ukraine.

Mystery Ships — Whale Hunting | Project Brazen

Russia’s Coral Energy Operation

Nine days before Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a man from Belize established Nord Axis, a new shipping company, in Hong Kong.

Coincidental timing? Maybe.

Soon after, Nord Axis became a major player in the Russian oil trade. Meanwhile, the Belizean man named on the paperwork had no idea what the company was or why it had been formed.

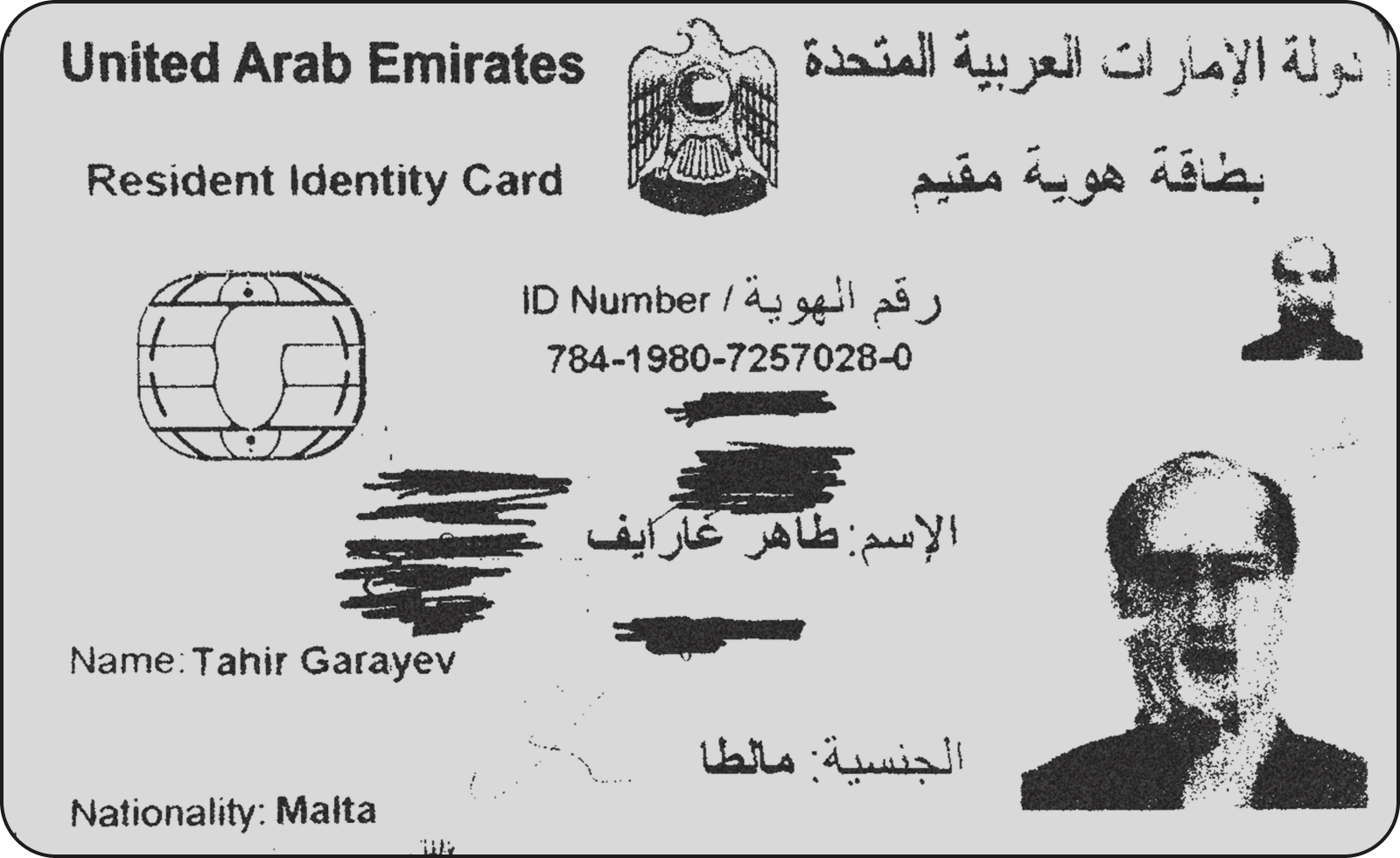

In reality, two Azerbaijani businessmen,

Tahir Garayev and

Etibar Eyyub

...were behind Nord Axis. Nord Axis was just one cog in their enormous, well-rigged machine, designed to make sure that Russia’s oil industry could keep on running smoothly as it waged war on Ukraine.

At the direction of Igor Sechin, CEO of Rosneft, Russia’s largest state-owned petroleum company, Garayev and Eyyub were allegedly building an underground network of shipping companies and a shadow fleet of poorly maintained ships that evade compliance and regulations — to fill the Kremlin’s coffers and circumvent sanctions against Russia.

A large part of this operation was allegedly controlled by Coral Energy, a single, sprawling conglomerate based in Singapore and Dubai. Coral Energy caught the attention of international authorities, including the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control. Documents viewed by Whale Hunting reveal Coral and five of its affiliated companies are among several firms under investigation by the authority on suspicion of illegally selling Russian oil.

Even the firm’s recent rebrand from Coral Energy to 2Rivers failed to conceal its reputation. Just this week, on Dec. 17, British prime minister Keir Starmer sanctioned 2Rivers to “further drain Putin’s war chest, by clamping down on the oil revenues he so desperately needs to fuel his illegal war.” 2Rivers did not respond to questions about the sanctions announcement, but a spokesperson for the company told The Wall Street Journal that “former employees” in Russia were using its name without permission, and that it would challenge the sanctions.

Sechin

PUTIN

Gutseriev

WHALE HUNTING

Whale Hunting has also viewed dozens of internal documents which show how Coral’s network and its key players have worked indirectly with Rosneft to keep the Russian oil shipping market afloat, despite their statements to the contrary.

Coral allegedly continues to control approximately 125 vessels for the shipment of oil — a number higher than previously reported.

The lifestyle of its traders, many of whom are related, is one of ultimate luxury. They travel by private jet and hang out between the suburbs of Geneva and the skyscrapers of Dubai.

To recognize the significance of Coral’s operation, one has to understand Russia’s complete dependence on oil. It is a linchpin of the Russian economy, and oil exports generate substantial foreign currency, giving the Kremlin considerable influence over global trade. Estimates suggest that oil profits contribute up to half of the Russian government’s annual revenue.

The world depends on it, too: if Russian oil were to disappear, the short-term effects would be felt nearly everywhere. Demand would outstrip supply, and the cost of everyday purchases would soar.

When Ukraine was invaded in February 2022, Western governments had a difficult question to answer: how could Russia be punished for its aggression without impacting the global economy? The result was a variety of different sanctions, largely price caps which sought to diminish the Kremlin’s resources. But the Russians found roundabout ways to supply oil through shadow fleets, with Coral leading the charge.

Whale Hunting has also viewed dozens of internal documents which show how Coral’s network and its key players have worked indirectly with Rosneft to keep the Russian oil shipping market afloat, despite their statements to the contrary.

Coral allegedly continues to control approximately 125 vessels for the shipment of oil — a number higher than previously reported.

The lifestyle of its traders, many of whom are related, is one of ultimate luxury. They travel by private jet and hang out between the suburbs of Geneva and the skyscrapers of Dubai.

To recognize the significance of Coral’s operation, one has to understand Russia’s complete dependence on oil. It is a linchpin of the Russian economy, and oil exports generate substantial foreign currency, giving the Kremlin considerable influence over global trade. Estimates suggest that oil profits contribute to up to half of the Russian government’s annual revenue.

The world depends on it, too: if Russian oil were to disappear, the short-term effects would be felt nearly everywhere. Demand would outstrip supply, and the cost of everyday purchases would soar.

When Ukraine was invaded in February 2022, Western governments had a difficult question to answer: how could Russia be punished for its aggression without impacting the global economy? The result was a variety of different sanctions, largely price caps which sought to diminish the Kremlin’s resources. But the Russians found roundabout ways to supply oil through shadow fleets, with Coral leading the charge.

shadow fleets outside of the Western

sphere of influence

billion from oil and gas exports

this year alone

Coral’s Roots

Coral had deep roots in oil trading, and in Russia. Tahir Garayev, an Azerbaijani national and dual citizen of Malta and Russia, founded the company in 2010. Back then, Coral was primarily trading crude oil from the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan. In 2014, Garayev hired Etibar Eyyub, who had long been based in Moscow and started establishing the company’s business in Russia. The same year, Coral incorporated in Dubai.

Over the next few years, TWO more Azerbaijani nationals were hired...

talat Safarov

Ahmed Karimov

In 2017, Coral decided to liquidate its office in Azerbaijan, but its business was booming: the company recorded revenues of over $3.5 billion in 2018.

In the years prior to the war, Eyyub and Garayev began developing a close relationship with Igor Sechin, the CEO of Rosneft. A hugely influential oligarch, Sechin is considered one of President Vladimir Putin’s closest allies.

Indirect Business

Coral built its shadow fleet fast, acquiring rusty tankers built in the early 2000s from China, Turkey and Greece. Such vessels may be old, but they aren’t cheap: each typically costs between $30 million and $40 million. Coral’s purchases were allegedly financed largely by loans from Russian banks.

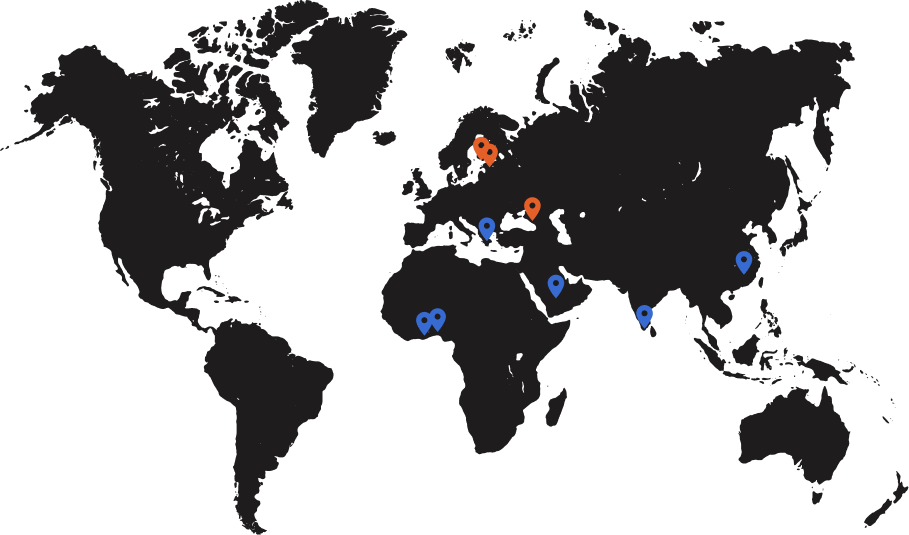

Coral’s new ships were given flags of countries with particularly lenient shipping regulations, making them hard to trace. Documents viewed by Whale Hunting show that 47 Coral vessels have a Gabonese flag. Others fly flags from Panama, Palau and the Cook Islands. It’s been reported that Coral has forged documents of origin.

There’s another big risk to a dark fleet: old ships, often not eligible for insurance, are at a much higher risk of accidents.

Documents viewed by Whale Hunting reveal that in October and November 2022, Coral spent over €100 million on fuel oil from Petrokim Trading Middle East and Asia DMCC in Dubai. Petrokim recently changed its name to Voliton.

Petrokim also had contracts with Nayara, an Indian petroleum company in which Rosneft happens to be the single largest stakeholder, owning nearly 50 percent.

In December 2022, the stakes got much higher:

…when a price cap imposed by G7 nations and their allies on Russian crude oil took effect. Russia could continue using Western oil tankers and insurance companies but only if it sold oil at or below $60 a barrel — substantially below benchmark prices.

A January 2023 contract between Petrokim and Nayara for over $48 million showed crude oil being traded at over $67 a barrel — above the new price cap. The ship used was named Daphne V and flew a Panama flag.

Allegedly, Coral also continued to find ways around the price cap working with operators and insurers in countries that did not sign onto the G7 agreement, such as ship management companies in India and Turkey and vessel owners in the Marshall Islands.

Coral sought out new customers outside the G7, supplying firms in Tunisia and South Africa. It continued to build relationships elsewhere: allegedly Eyyub and Garayev travelled to India and China with Sechin. Shipping data viewed by Whale Hunting shows vessels chartered by Coral exporting oil to Chinese, Indian and West African ports.

A Lethal Mosquito Bite

At the same time, Coral seemed to be moving money between its own companies. In January 2023, the company requested a €313 million dollar refund from Petrokim, the company also named Voliton and affiliated with Coral . In June, Pontus Trading — another Coral affiliate company — paid Voliton over $300 million. Both firms were registered to the Jumeirah Lakes Tower in Dubai. The barrels sold were all priced over the cap at $66, and the ships headed to India under Gabonese or Panamanian flags.

Then, it got

weirder:

In Dubai, Russian trader Ilya Pereguda was mysteriously struck down by pneumonia a few months after being tasked with helping Coral enter the Tanzanian market. The official narrative was that he died of an illness caused by a mosquito bite, but Africa Intelligence reported that there was speculation he had been poisoned.

Despite Pereguda’s death, Coral’s business with Tanzania took off, and the company won at least six contracts to supply fuel to the East African country.

In May, another shell company, Pura Vida Holding Limited, was incorporated in the United Arab Emirates. It became the ultimate parent company of Coral and its affiliates. Pura Vida Holding’s shareholders were two of Coral’s existing team members — Talat Safarov and Ahmad Karimov — plus a new face, Anar Madatli, the son of Azerbaijan’s former ambassador to Ukraine and the brother-in-law of Coral’s founder Garayev.

Later that year, as Garayev was holding meetings with Rosneft officials, the dark fleet operation was coming under increasing pressure. In November, shipowner Tonzip Maritime brought a million-dollar claim against Coral in California. It claimed that Coral had chartered a vessel to ship oil from a company linked to Russian oil tycoon Mikhail Gutseriev, who is sanctioned by the EU for his ties to Belarus.

In December, the U.S. sanctioned two allegedly Coral-affiliated entities, Voliton DMCC and Bellatrix Energy Limited. The Treasury said that Bellatrix had “sharply increased its share of the trade of Russian oil since the price cap policy was implemented.”

Shipping data viewed by Whale Hunting shows that Bellatrix chartered 13 journeys in 2023, carrying over 3.7 million tons of crude oil or gas oil diesel. All journeys originated in Russian towns, either Primorsk, Tuapse or Ust Luga. Destinations were ports in India, Greece, Ghana, China, Saudi Arabia and Benin. The flags on the ships were those of Gabon or Panama.

A recent Le Monde investigation found that between February 2023 and February 2024 at least 41 cargoes of petroleum oil were sold by Coral to Swiss oil trading giant Trafigura Group, now headquartered in Singapore —sales which may have violated European and American sanctions, exceeding the price caps. Whale Hunting can also reveal that Coral and Trafigura have a close relationship and have even shared employees.

One man with a lot of overlap is Otabek Karimov. A former top executive at Rosneft, he left the company in May 2022. He is believed to have played a key role in the development and management of Coral’s trading operations before being hired by Trafigura in Dubai this June.

A Trafigura spokesperson told Whale Hunting that the company “has complied and continues to comply with the Price Cap Framework, as well as all sanctions laws applicable to it.” In response to a question about Karimov’s hire, the spokesperson said “we do not comment on personnel matters.”

russian ports of origin

Primorsk | Tuapse | Ust Luga

COUNTRIES OF DESTINATION

India | Greeece | Ghana | China | Saudi Arabia | Benin

The Rebranding

Europeans have also allegedly been involved in Coral’s operation. This year, Coral hired Swiss citizen Patrick Cotasson, who was previously at UniCredit bank in Geneva. The director of Coral affiliate Apeiron is a British man named Timothy Mark Peet, who was also formerly the nominal owner of Coral. Peet’s LinkedIn profile suggests he has been at Apeiron since 2021 and working in Dubai for at least a decade.

This spring brought new challenges for Coral: in March, Dubai’s main state-owned bank, Emirates NBD, ordered the closure of accounts belonging to Coral, Voliton, Pontus and another company associated with Eyyub.

One of Coral’s vessels, named HANA, was sanctioned by the EU on June 25, 2024. But that doesn’t appear to have stopped it operating. Shipping data shows that after the sanctions it was renamed Kavya, and its flag was changed from Gabon to Tanzania.

Then, on July 29, Coral announced its rebranding to 2Rivers Group following the successful completion of a management buyout. The new management team included those previously involved in Coral operations: Anar Madatli, Talat Safarov, Ahmed Karimov and Patrick Cotasson.

2Rivers now allegedly employs 110 people,

...particularly in Dubai, and expects its sales to total $11 billion this year. In the press release, Karimov insisted that 2Rivers was a new venture.

But the company’s roots remain entangled with Coral: according to a certificate viewed by Whale Hunting, just two weeks before the rebranding, Pura Vida, Coral’s parent company, became the 85% shareholder of Novus Middle East, another company affiliated with Coral and said to be Garayev’s holding company.

“The rebranding to 2Rivers is much more than just a name change; it represents our evolution and vision for the future,” he said. “Rivers are powerful symbols of energy, renewal and connection.”

Mystery Ships

Got a question or a tip for us? Get in touch by emailing us at whalehunting@projectbrazen.com. You can also contact us securely here.

- BY GEORGIA GEE & ARNAV BINAYKIA -

- WHALE HUNTING -

- PROJECT BRAZEN -

- BRAZEN

Mystery Ships — Whale Hunting | Project Brazen is proudly powered by WordPress